Scientists discover rare genetic condition that attacks kids’ immune systems

What Is Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)?

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare, severe blood disorder that causes blood clots to form in small blood vessels.

TTP can affect children and adults. People may inherit the condition or develop it through certain health conditions or medical treatments.

The blood clots that form with TTP can restrict blood flow to the organs, leading to various health problems. Without prompt treatment, TTP can be life threatening.

This article looks at TTP symptoms, causes, diagnosis, treatment, and outlook.

TTP is a rare blood disorder that causes blood clots to form in the body's small blood vessels. These blood clots can restrict or block blood flow to the organs, causing damage and affecting organ function.

Platelets are blood cells that help the blood clot to prevent bleeding. The formation of blood clots with TTP uses up platelets, which means the blood does not have enough platelets to form the necessary clots. This can lead to bruising and bleeding under the skin.

Thrombotic refers to the formation of a blood clot in a blood vessel, and thrombocytopenic means a reduced platelet count. Purpura is the term for the bruises that occur due to bleeding under the skin.

TTP also destroys red blood cells faster than the body can produce them, causing hemolytic anemia.

TTP can be life threatening, and without treatment, it may lead to serious complications, including stroke or brain damage.

TTP occurs when people have a severe deficiency of the ADAMTS13 enzyme, a protein in the blood that controls blood clotting. Without enough ADAMTS13, excess blood clots form.

People may inherit TTP or acquire it during their lifetime. They can also inherit a faulty ADAMTS13 gene, which means the gene produces an ADAMTS13 enzyme that does not function properly.

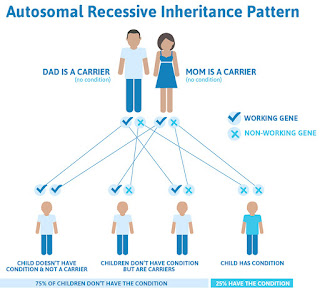

In most diagnoses of inherited TTP, each parent has one copy of the faulty ADAMTS13 gene, but they do not have any TTP signs or symptoms. People with inherited TTP have two copies of the ADAMTS13 mutation, as they receive one copy of the genetic mutation from each parent.

People with acquired TTP have a normal ADAMTS13 gene, but the body creates antibodies that prevent the ADAMTS13 enzyme from working correctly. This may happen due to certain health conditions or medical treatments.

Inherited TTP usually occurs in infants and children. Acquired TTP usually develops in adulthood but can also occur in children.

Risk factors for developing TTP include:

A 2016 study notes that Black people are at an increased risk of developing TTP and suggests that genetic factors may be contributors to their increased risk.

Certain medications and substances may cause TTP, including:

A doctor will assess any symptoms of TTP involves a doctor performing a physical examination, as well as requesting and evaluating personal and family histories.

Signs of TTP may appear differently in each person and can be similar to those in other conditions. If a doctor suspects TTP, they will typically order a range of tests, such as:

People with TTP need immediate treatment, as delayed treatment may increase the risk of life threatening complications. Doctors may begin treatment before the results of ADAMTS13 testing can confirm a diagnosis.

Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) is the first-line treatment for acquired TTP. TPE replaces plasma, the liquid component of blood, with healthy donor plasma.

The new plasma supplies the right amount of ADAMTS13 enzyme and removes antibodies that damage the enzyme. People will have TPE daily until it resolves the issues from TTP.

Alongside TPE, people will also typically receive immunosuppressive drugs, such as glucocorticoids or rituximab, to target the antibodies that attack the ADAMTS13 enzyme.

Doctors use plasma infusion to treat inherited TTP. This delivers donor plasma intravenously to replace the ADAMTS13 enzyme deficiency.

In 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug Adzynma for adults and children with inherited TTP.

Adzynma is a genetically engineered version of the ADAMTS13 enzyme. It works to replace the enzyme or reduce the risk of TTP symptoms, and may be a safe and effective TTP treatment.

If standard TTP treatments are not effective, healthcare professionals may prescribe surgery to remove the spleen. The spleen is an abdominal organ that produces antibodies that block the effects of the ADAMTS13 enzyme.

TTP is a rare blood disorder that causes blood clots to develop in small blood vessels. It can damage organs and lead to them not working properly.

It is important that people contact a doctor immediately if they have any symptoms of TTP. The condition can be life threatening, but prompt treatment can help prevent severe or fatal complications.

Treatment may include plasma replacement therapies, medications, and in some cases, surgery to remove the spleen.

Man Died From Blood Clot After Wrongly Receiving Covid Vaccine, Review Finds

A man died from a blood clot after having an adverse reaction to a Covid-19 jab he was wrongly given, a review has found.

Jack Last, 27, died in hospital in April 2021 after he was given the AstraZeneca (AZ) vaccine, which he was invited to receive a month earlier.

But a report commissioned by NHS Suffolk and North East Essex Integrated Care Board (ICB) found Mr Last was only invited because he had been incorrectly classified as living with his parents on records held by the Suffolk GP Federation.

The report, published on Tuesday, also found there was a missed opportunity to give Mr Last the appropriate X-rays and treatment while he was at West Suffolk Hospital in Bury St Edmunds.

It was known at the time of his jab that the AstraZeneca vaccine, in rare cases, could have side effects on those in his age group, including blood clots in veins and arteries.

The report concluded Mr Last's death was "a consequence of a combination of system shortcomings, human error, and tragic unfortunate timing".

A previous illness diagnosed to one of Mr Last's parents years before the vaccination programme, which was not active at the time, also remained on the GP record of the Suffolk GP Federation.

This meant he was included among those deemed eligible for the Covid-19 vaccine as their clinical condition was described as "at-risk".

An error that classed Mr Last's own telephone number as that of his parents' landline gave him household contact status, which also made him eligible for the vaccine.

Mr Last received the AZ vaccine on March 30 2021, shortly before guidance on giving the jab changed and alternative vaccines were recommended for his age group.

The report said: "If Jack had not been invited to have the AZ vaccine early, he would have been in a much later cohort (starting June 8 2021), by which time people under 30 were to be offered Pfizer or Moderna vaccines."

Mr Last began to feel unwell a week later and had severe headache, vomited and was sensitive to light.

After going to West Suffolk Hospital, he was reported by a radiologist as having no brain abnormalities after he underwent a plain CT head scan.

However, a review demonstrated there were slight abnormalities that were missed which could have identified a blood clot in his brain.

A further scan the following day clearly identified a blood clot, meaning there was a delay in treatment of approximately 15 hours.

This was unlikely to have changed Mr Last's outcome but was a missed opportunity to have started the correct treatment sooner, the report found.

He was then transferred to Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, with the report finding the treatment he received there to be appropriate and of a high standard.

Mr Last's condition deteriorated and he died of vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia on April 20 2021.

Medical director of the Suffolk and North East Essex ICB, Dr Andrew Kelso, said: "Our thoughts remain with the family of Jack and have been throughout this very tragic case.

"On behalf of all system partners, we are truly sorry for what has happened and for the loss, heartbreak and distress they must be experiencing.

"Due to the seriousness of what happened, we immediately commissioned an independent review to fully understand what led to this tragedy and to identify learning. We also wanted to give the family all the answers to their questions.

"This independent review allowed the system to look at the incident from beginning to end, without the restrictions of organisational boundaries and without prejudice."

Risk Of Blood Clots More Likely With Sickle Cell Trait, But Still Low

People with sickle cell trait (SCT), those who carry a mutation in one copy of the HBB gene but do not have sickle cell disease (SCD), are at an increased risk of blood clots compared with people who don't carry the trait regardless of racial or ethnic background, according to a study.

Still, the researchers said, the risk of these blood clots was low, occurring in just over 2% of people carrying SCT.

The study, "Ancestry-Independent Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Individuals with Sickle Cell Trait vs. Factor V Leiden," was published in Blood Advances.

"I hope this study informs health professionals, particularly hematologists, that when thinking about risks related to SCT, they need to be looking at all populations, not just one group," Vence L. Bonham Jr., acting deputy director of the National Human Genome Research Institute and a study author, said in a press release from the American Society of Hematology. "SCT is understudied, and this is an area of opportunity for more research," Bonham said.

SCD is caused by mutations in both copies of the HBB gene, leading to the production of an abnormal version of hemoglobin, the protein that helps red blood cells carry oxygen. People who carry only one mutated HBB gene copy are considered to have SCT. Also known as sickle cell carriers, these individuals generally lead normal lives without any symptoms.

Risk of blood clotsPeople with SCT may be at an increased risk for venous thromboembolisms (VTE), when a blood clot forms in a vein. This may include pulmonary embolism, in which a clot forms in the lungs, or deep vein thrombosis, in which the clot forms in deep veins, often in the legs.

Previous studies on the link were largely limited to Black populations. It is often wrongfully assumed that SCT only affects Black people, leading to discrimination in research, according to the authors.

"SCT is erroneously associated only with Black individuals, even though it is found in very diverse populations," said Rakhi Naik, MD, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University and the study's senior author. "When we do research within a specific population, we often make the incorrect assumption that the genetic trait is found only in that population, even though it is found quite broadly."

A similar bias is seen with heterozygous factor V Leiden (FVL), the most common inherited blood clotting disease, which is often assumed to affect only white people, the researchers said.

They decided to conduct a large analysis of VTE in people with sickle cell trait and FVL, regardless of race or ethnicity. They leveraged genetic data from 23andMe, using DNA samples from more than 4 million adults who submitted self-reported data about their history of VTE.

Results showed that the prevalence of sickle cell trait in this group was 0.46%, affecting just over 19,000 people, with the highest prevalence in people of African ancestry (7%), Latino ancestry (0.67%), and South Asian ancestry (0.16%). The prevalence of FVL was 4.45%, affecting more than 186,000 people.

A history of VTE was reported by 2.57% of people with SCT, compared with 2.25% in people without it. Among those with FVL, VTE was reported by 6.93%, compared with 2.04% in those without FVL.

In final statistical analyses, the risk of VTE was found to be 1.45 times higher in people with sickle cell trait relative to those without it, regardless of race or ethnicity. Still, the risk of VTE was even higher in people with FVL, who were 3.3 times more likely to experience VTE than those without FVL.

Unique clotting mechanismThe most common type of VTE experienced in people with SCT was a pulmonary embolism, whereas deep vein thrombosis predominated in FVL.

This difference "points to a unique mechanism of clotting in SCT, which warrants further research," Naik said.

The researchers said they hope the findings inform better clinical practice guidelines for SCT management. "Very few clinicians know how to counsel someone with SCT," Naik said. "This study shows that SCT in itself is not a disease. It's a risk factor like FVL, and the risk is still very small."

Study limitations were the fact that VTE information was self-reported, and that data on other factors, such as surgery or injury, that could provoke blood clots were not available.

"Our study provides important ancestry-independent risk estimates for VTE in individuals with SCT," the researchers wrote. "These data may inform clinical practice guidelines, future research, and public health initiatives in SCT," they added.

Comments

Post a Comment