Southern Regional Meeting 2017, New Orleans, LA, February 11-13 ...

Woman Is Diagnosed With Down Syndrome As An Adult After Warning Signs

Mom-of-three Diagnosed With Mosaic Down Syndrome During Pregnancy

SHARE

SHARE

TWEET

SHARE

What to watch next

Video Of Joe Biden's Memorial Day Salute Fail Goes Viral

NewsweekNew Mexico Man Confesses To Murdering Landlord 14 Years Later

NewsweekTomi Lahren Blasted For Saying 'Straight, White' Men Can't Have An Opinion

NewsweekPrince Harry and Meghan Car Chase Could Signal U.S. Reputational Problem

NewsweekWatch Chihuahua That Loves To Suck Thumbs

NewsweekAttorney Arrested Over String of Rapes and Kidnappings In Boston

NewsweekVideo Captures 'Manhattanhenge' Phenomenon in NYC

NewsweekCalvin Klein Ad Featuring Bearded Trans Man Resurfaces Amid Bud Light Furor

NewsweekMaricopa County Fact-Checks Election Video Pushed by Kari Lake Fans

NewsweekSan Francisco Faces Retail Exodus As Old Navy Becomes Latest To Flee Area

NewsweekCat's Impressive Boxing Technique Gives 'Southpaw' Whole New Meaning

NewsweekPrincess Charlotte's Inherited 'Hair Flick' Spotted By Fans

NewsweekThese Noteworthy Candidates Have Formally Announced 2024 Presidential Bids

NewsweekGreat White Sharks Filmed Feasting on Dolphin Over Memorial Day Weekend

NewsweekUkraine Counteroffensive Will Be 'Impressive': Lindsey Graham

NewsweekLululemon Backlash After Firing Staff Who Stopped Thieves: 'Woke Go Broke'

NewsweekClick to expand

UP NEXT

At the age of 23, a mom has discovered a condition she's lived with her entire life without realizing, and the reason why she conceived three babies with Down Syndrome.

Mom-of-three, Ashley Zambelli has experienced an inordinate amount of pain already, after suffering four miscarriages and finding out that two of her daughters have Down Syndrome. Zambelli, from Michigan, had no explanation for the miscarriages or why she conceived three babies with Down Syndrome, which is also referred to as Trisomy 21, one of which she miscarried.

The stay-at-home mom explained to Newsweek that she found out at 14 weeks pregnant that her third daughter, Katherine, had Trisomy 21, and it was "pretty rare to conceive three babies with Down Syndrome."

She continued: "I have had seven pregnancies, four of which were miscarriages. One of my miscarriages was a son with Trisomy 21. We found out our first-born, Lillian, had Trisomy 21 while pregnant with her. Then fast forward to our third daughter, who we found out also had Trisomy 21 while 14 weeks pregnant."

Zambelli was referred for genetic testing and a buccal smear test of a sample from her cheek led to a diagnosis of Mosaic Down Syndrome, as some of her cells had the usual 46 chromosomes and others had 47.

What Is Mosaic Down Syndrome?

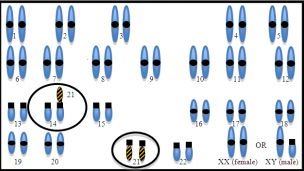

Most babies are born with 46 chromosomes but babies with Down Syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21. For this reason, Down Syndrome is referred to as Trisomy 21.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 95 percent of people with Down Syndrome have Trisomy 21, however there are two other types which occur less frequently. Translocation Down Syndrome occurs in around three percent of cases, occurring when an extra part of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome.

The third type is Mosaic Down Syndrome, affecting two percent of people with Down Syndrome. This means that some cells have three copies of chromosome 21, and others have two copies. The CDC notes that children born with Mosaic Down Syndrome might have fewer physical attributes of the condition because some of their cells have a typical number of chromosomes.

Signs and symptoms of Down Syndrome include a lower IQ, small ears, shortness, a flatter face, hearing loss, heart defects, sleep apnea and visual impairments.

© @ashleyzambelli Left is Ashley Zambelli with her partner and their oldest two daughters, Lillian and Evelyn. Right is Zambelli with her third daughter, Katherine. Zambelli has suffered four miscarriages, which she couldn't explain before her diagnosis. @ashleyzambelliDr. Xiao-Fei Kong is an expert who has studied Down Syndrome extensively and now works at UT Southwestern Medical Center. Having worked with Down Syndrome patients for more than 10 years, Kong told Newsweek he's "only seen a few patients" with Mosaic Down Syndrome, because of its rarity.

Kong said: "People with Down Syndrome have three copies of chromosome 21 in all their cells, but those with Mosaic Down Syndrome carry an additional copy in only some cells.

"It is unusual for an adult to be diagnosed with Mosaic Down Syndrome as the condition is more commonly discovered during pregnancy, through genetic testing."

While certain prenatal testing can uncover Mosaic Down Syndrome, Kong adds that if the correct approach isn't taken, "the condition could go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed."

"Although the diagnosis of Mosaic Down Syndrome sounds scary, many people with this condition have fulfilling lives. Nevertheless, additional considerations may be required in their education, family planning and disease screening. I hope that we can foster increase social support for this group."

'Had I Never Had Kids, I Would Have Never Known"

Although Zambelli can now see the effects of the condition on her, she admits that she had no idea that she had Mosaic Down Syndrome until her diagnosis on February 17, 2023.

"While this syndrome has many conditions associated with it, it affects everyone differently," she told Newsweek. "For me personally, I have temperature dysregulation, patellar dislocations, pelvic congestion disorder, comprehensive difficulties when I was a child, sensory issues and small ears.

"Had I never had kids, I would have never known about my genetic condition. Outside of myself and two of my daughters, no one else in my family has Down Syndrome as far as I know."

© @ashleyzambelli Left is Ashley Zambelli holding her second daughter, Evelyn who doesn't have Down Syndrome. Right is Zambelli's oldest daughter, Lilian. Zambelli's oldest and youngest daughters both have Down Syndrome, but her second child doesn't. @ashleyzambelliThe diagnosis came as a complete shock to Zambelli, who was 28 weeks pregnant at the time, but she hasn't let it change the way she views herself. She's utilized her surprise by sharing her experience with social media users instead.

"My diagnosis hasn't changed much about how I view myself or how I live my life, though it brought me to spread more awareness on Down Syndrome," she said. "I've always been an open book and love sharing my life experiences online.

"I have noticed that people aren't afraid to show their true colors after finding out about my diagnosis, needless to say, some of which aren't pretty. Even people in my own community have asked me for proof of my diagnosis because they don't think I look Down Syndrome enough.

"Society has stereotyped Down Syndrome into something that it's not."

After Zambelli shared her diagnosis story on TikTok (@ashleyzambelli) in February, her video has been viewed more than 6.5 million times, and received over 272,000 likes.

Among the 1,300 comments on the video, one person wrote: "That must have been such a shock, but also such a relief to have some answers. I don't think I've ever heard of this diagnosis as an adult."

Another comment reads: "I wonder how many people have this without ever finding out for their whole lives."

Is there a health issue that's worrying you? Let us know via health@newsweek.Com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured on Newsweek.

Related Articles

Start your unlimited Newsweek trial

This Mom Posted About Wanting To Find Friends For Her 24-year-old Son With Down Syndrome. The Overwhelming Support Shocked Her.

Christian Bowers, now 24, had many friends in high school, but after graduating five years ago, it's been hard to find good friends. Christian has Down syndrome, and his mom, Donna Herter, said his lack of friends was making him feel depressed.

"[He was] just constantly asking where his friends are, why doesn't anybody want to come over and spend some time with him," Herter, who lives near Rochester, Minnesota, told CBS News. "We would go to Walmart or the store and he would invite half the store to come home with us and play video games with us. And of course, nobody would. And he just doesn't understand why."

Herter didn't know where to turn. So, she posted on Facebook. "I just basically said that I was looking for a young man, between the ages of 20 and 28, local," she said. "I told them that I'd pay them $80 for two hours to basically just hang out and play video games with him. All he really wants is just a guy friend to do guy stuff with."

Christian Bowers has Down syndrome, and his mom, Donna Herter, said the lack of friends was making him feel depressed. She didn't know where to turn. So, she posted on Facebook. Donna HerterHerter is a nurse, working the overnight shift. She sent the post at 4 a.M. Before ending her workday. And when she woke up, it had about 5,000 comments.

"I was freaking out. My hands were shaking, I was sweating. I was just looking for some local guys, I didn't want to invite like the entire world into our house," she said. She was overwhelmed and thought about deleting the post – but a friend told her to look at the replies first.

She saw parents offering suggestions, others volunteering to help — and some parents of children with special needs asking for advice themselves.

Donna Herter interviewed local guys in Minnesota and found seven that now visit Christian on a rotating schedule. Donna HerterFriendships are important for people born with Down syndrome, but leaving school and becoming an adult may make maintaining those relationships difficult. Some adults with Down syndrome may face barriers, like not being able to drive to see their friends, according to the National Down Syndrome Society, or NDSS.

Having social relationships is important for everyone's mental health – including those with Down syndrome. According to a 2018 study in Australia, young adults with Down syndrome with at least three social relationships often showed a significantly better quality of life, according to an assessment by researchers.

NDSS says it's "vitally important" for adults with Down syndrome to plan for how they will socialize once they leave school, and clubs, volunteering or further education are good options.

There are many organizations that help people with Down syndrome find opportunities to be social and to work.

Herter said Christian attends events for people with special needs, but he "craves a friendship with somebody who is neurotypical. He doesn't want to only hang out with somebody with special needs."

"And I've never asked him, but I assume because it kind of makes him feel normal, just for an hour or two. 'Hey, somebody who doesn't have Down syndrome wants to hang out with me,'" she said.

After interviewing a few local guys in Wentzville, Minnesota, Donna narrowed it down to seven who now visit Christian visit once a week on a rotating schedule.

James Hasting was one of the men she chose. He saw the post because a friend tagged him in it. "When I first read the post, I was heartbroken that she felt she needed to pay people to be friends with Christian," Hasting told CBS News.

Hasting said he works with people with disabilities and it's something he has a passion for. He said he's visited Christian three times so far and they usually play video games or watch a movie.

"Christian has taught me to look at the world for more than what we see on the surface," Hasting said. "Because though on the surface we may look different, deep down we all have similarities and getting along should be easy."

He said he hopes this story teaches others it's OK to be different. "Just because someone is different than what you are used to, it doesn't mean that they aren't the same at heart."

Herter's post also lead to more opportunities for Christian – people around the country send him gifts, he was invited to hang out with local firefighters, was named honorary mayor of nearby Wentzville for the day and went bowling with local marines.

"He every night goes to bed with a smile on his face. He tells everybody about his new friends. He gets so excited talking about life now and what he's doing," Herter said. "But I still think the one thing he likes the most is that one-on-one. Just that guy coming over."

Herter hopes to inspire others to form friendships — because you never know how much it means to someone. "Everybody needs a friend," she said. "I thought about it one day. I just sat there and I was like, 'What if I have zero friends? What if I had literally not one person to call, to talk to, to hang out, to have lunch with.' And man, it just really hit me thinking about that, how lonely that would be."

"Knowing there's so many people out there that are wanting that relationship, or wanting a friend, I really hope people reach out in their community and find out where those people are, how to get ahold of them, how to hang out with them."

Dad creates fully accessible theme park inspired by daughter

93-year-old grandma and grandson visit every U.S. National park

Couple celebrates milestone on date

6-year-old's morning routine goes viral

10-year-old's financial advice to parents

MoreCaitlin O'KanePeople With Down Syndrome Are Living Longer, But The Health System Still Treats Many As Kids

Marilyn Lesmeister and her daughter Samantha "Sammee" Lesmeister after Sammee's riding lesson at Remember to Dream therapeutic riding center in Cole Camp, Mo. Sammee Lesmeister is one of a growing number of adults living with Down syndrome. (Christopher Smith/KFF Health News)

MONTROSE, Mo. — It took Samantha Lesmeister's family four months to find a medical professional who could see that she was struggling with something more than her Down syndrome.

The young woman, known as Sammee, had become unusually sad and lethargic after falling in the shower and hitting her head. She lost her limited ability to speak, stopped laughing and no longer wanted to leave the house.

General-practice doctors and a neurologist said such mental deterioration was typical for a person with Down syndrome entering adulthood, recalled her mother, Marilyn Lesmeister. They said nothing could be done.

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

The family didn't buy it.

Marilyn researched online and learned the University of Kansas Health System has a special medical clinic for adults with Down syndrome. Most other Down syndrome programs nationwide focus on children, even though many people with the condition now live into middle age and often develop health problems typically associated with seniors. And most of the clinics that focus on adults are in urban areas, making access difficult for many rural patients.

The clinic Marilyn found is in Kansas City, Kan., 80 miles northwest of the family's cattle farm in central Missouri. She made an appointment for her daughter and drove up.

The program's leader, nurse practitioner Moya Peterson, carefully examined Sammee Lesmeister and ordered more tests.

"She reassured me that, 'Mom, you're right. Something's wrong with your daughter,'" Marilyn Lesmeister said.

With the help of a second neurologist, Peterson determined Sammee Lesmeister had suffered a traumatic brain injury when she hit her head. Since that diagnosis about nine years ago, she has regained much of her strength and spirit with the help of therapy and steady support.

Sammee, now 27, can again speak a few words, including "hi," "bye," and "love you." She smiles and laughs. She likes to go out into her rural community, where she helps choose meals at restaurants, attends horse-riding sessions at a stable, and folds linens at a nursing home.

Without Peterson's insight and encouragement, the family likely would have given up on Sammee's recovery. "She probably would have continued to wither within herself," her mother said. "I think she would have been a stay-at-home person and a recluse."

'A Whole Different Ballgame'

The Lesmeisters wish Peterson's program wasn't such a rarity. A directory published by the Global Down Syndrome Foundation lists just 15 medical programs nationwide that are housed outside of children's hospitals and that accept patients with Down syndrome who are 30 or older.

The United States had about three times as many adults with the condition by 2016 as it did in 1970. That's mainly because children born with it are no longer denied lifesaving care, including surgeries to correct birth defects.

Adults with Down syndrome often develop chronic health problems, such as severe sleep apnea, digestive disorders, thyroid conditions and obesity. Many develop Alzheimer's disease in middle age. Researchers suspect this is related to extra copies of genes that cause overproduction of proteins, which build up in the brain.

"Taking care of kids is a whole different ballgame from taking care of adults," said Peterson, the University of Kansas nurse practitioner.

Sammee Lesmeister is an example of the trend toward longer life spans. If she'd been born two generations ago, she probably would have died in childhood.

She had a hole in a wall of her heart, as do about half of babies with Down syndrome. Surgeons can repair those dangerous defects, but in the past, doctors advised most families to forgo the operations, or said the children didn't qualify. Many people with Down syndrome also were denied care for serious breathing issues, digestive problems or other chronic conditions. People with disabilities were often institutionalized. Many were sterilized without their consent.

Such mistreatment eased from the 1960s into the 1980s, as people with disabilities stood up for their rights, medical ethics progressed and courts declared it illegal to withhold care. "Those landmark rulings sealed the deal: Children with Down syndrome have the right to the same lifesaving treatment that any other child would deserve," said Brian Skotko, a Harvard University medical geneticist who leads Massachusetts General Hospital's Down Syndrome Program.

The median life expectancy for a baby born in the U.S. With Down syndrome jumped from about four years in 1950 to 58 years in the 2010s, according to a recent report from Skotko and other researchers. In 1950, fewer than 50,000 Americans were living with Down syndrome. By 2017, that number topped 217,000, including tens of thousands of people in middle age or beyond.

The population is expected to continue growing, the report says. A few thousand pregnant women a year now choose abortions after learning they're carrying fetuses with Down syndrome. But those reductions are offset by the increasing number of women becoming pregnant in their late 30s or 40s, when they are more likely to give birth to a baby with Down syndrome.

Skotko said the medical system has not kept up with the extraordinary increase in the number of adults with Down syndrome. Many medical students learn about the condition only while training to treat pediatric patients, he said.

Few patients can travel to specialized clinics like Skotko's program in Boston. To help those who can't, he founded an online service, Down Syndrome Clinic to You, which helps families and medical practitioners understand the complications and possible treatments.

'If They Say It Hurts, I Listen'

Charlotte Woodward, who has Down syndrome, is a prominent advocate for improved care. She counts herself among the tens of thousands of adults with the condition who likely would have died years ago without proper treatment. Woodward, 33, of Fairfax, Va., had four heart surgeries as a child and then a heart transplant in her 20s.

Woodward, who is an education program associate for the National Down Syndrome Society, has campaigned to end discrimination against people with disabilities who need organ transplants.

She said her primary care doctor is excellent. But she has felt treated like a child by other health care providers, who have spoken to her parents instead of to her during appointments.

She said many general-practice doctors seem to have little knowledge about adults with Down syndrome. "That's something that should change," she said. "It shouldn't just be pediatricians that are aware of these things."

Woodward said adults with the condition should not be expected to seek care at programs housed in children's hospitals. She said the country should set up more specialized clinics and finance more research into health problems that affect people with disabilities as they age. "This is really an issue of civil rights," she said.

Advocates and clinicians say it's crucial for health care providers to communicate as much as possible with patients who have disabilities. That can lead to long appointments, said Brian Chicoine, a family practice physician who leads the Adult Down Syndrome Center of Advocate Aurora Health in Park Ridge, Ill., near Chicago.

"It's very important to us that we include the individuals with Down syndrome in their care," he said. "If you're doing that, you have to take your time. You have to explain things. You have to let them process. You have to let them answer. All of that takes more time."

Time costs money, which Peterson believes is why many hospital systems don't set up specialized clinics like the ones she and Chicoine run.

Peterson's methodical approach was evident as she saw new patients on a recent afternoon at her Kansas City clinic. She often spends an hour on each initial appointment, speaking directly to patients and giving them a chance to share their thoughts, even if their vocabularies are limited.

Her patients that day included Christopher Yeo, 44, who lives 100 miles away in the small town of Hartford, Kan. Yeo had become unable to swallow solid food, and he'd lost 45 pounds over about 1½ years. He complained to his mother, Mandi Nance, that something "tickled" in his chest.

During his exam, he lifted his shirt for Peterson, revealing the scar where he'd had heart surgery as a baby. He grimaced, pointed to his chest, and repeatedly said the word "gas."

Peterson looked Yeo in the eye as she asked him and his mother about his discomfort.

The nurse practitioner takes seriously any such complaints from her patients. "If they say it hurts, I listen," she said. "They're not going to tell you about it until it hurts bad."

Yeo's mother had taken him to a cardiologist and other specialists, but none had determined what was wrong.

Peterson asked numerous questions. When does Yeo's discomfort seem to crop up? Could it be related to what he eats? How is his sleep? What are his stools like?

After his appointment, Peterson referred Yeo to a cardiologist who specializes in adults with congenital heart problems. She ordered a swallowing test, in which Yeo would drink a special liquid that appears on scans as it goes down. And she recommended a test for Celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder that interferes with digestion and is common in people with Down syndrome. No one had previously told Nance about the risk.

Nance, who is a registered nurse, said afterward that she has no idea what the future holds for their family. But she was struck by the patience and attention Peterson and other clinic staff members gave to her son. Such treatment is rare, she said. "I feel like it's a godsend. I do," she said. "I feel like it's an answered prayer."

'Like a Person, and Not a Condition'

Peterson serves as the primary care provider for some of her patients with Down syndrome. But for many others, especially those who live far away, she is someone to consult when complications arise. That's how the Lesmeisters use her clinic.

Mom Marilyn is optimistic Sammee can live a fulfilling life in their community for years to come. "Some people have said I need to put her in a home. And I'm like, 'What do you mean?' And they say, 'You know — a home,'" she said. "I'm like, 'She's in a home. Our home.'"

Sammee's sister, who lives in Texas, has agreed to take her in when their parents become too old to care for her.

Marilyn's voice cracked with emotion as she expressed her gratitude for the help they have received and her hopes for Sammee's future.

"I just want her to be taken care of and loved like I love her," she said. "I want her to be taken care of like a person, and not a condition."

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Read more stories like this one. Sign up for Disability Scoop's free email newsletter to get the latest developmental disability news sent straight to your inbox.

Comments

Post a Comment