Hereditary thrombocytopenia: Common types and FAQs

Combined Screening Test For Down's, Edwards' And Patau's Syndrome

As part of your NHS antenatal care, from about 12 weeks into your pregnancy, you will be offered various scans, checks and tests to make sure that your baby is healthy and developing well. One of these tests, called the combined screening test, checks for Down's, Edwards' and Patau's syndromes.

You will be asked whether you want to have this test or not; you can refuse and no one will mind. And we reckon it's worth arming yourself with some info before you're asked to make that decision.

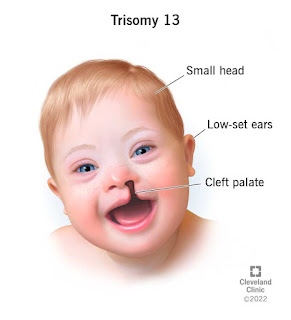

What are these syndromes exactly?All 3 syndromes are genetic disorders where a baby has an extra copy (or part of a copy) of a particular chromosome, leading to particular set of disabilities or growth problems. Both Edwards' and Patau's syndrome are very rare – and more serious – than Down's syndrome.

It's highly unlikely. It's thought that Down's syndrome affects 1 in every 500 pregnancies, while the much rarer Edwards' syndrome affects 1 in every 1500 pregnancies. Patau's syndrome is extremely rare and is diagnosed in fewer than 200 babies a year.

Will the combined screening test tell me for sure either way?No, we're afraid it's a little bit more complicated than that – as this test will only tell you whether there is a high chance or a low chance of your having a baby with Down's, Edwards' or Patau's.

More like this

If you're told your chance of having a baby with any of these conditions is low (as the vast majority of women are), you won't need any further testing; if you're told your change is high, you will probably be offered further, more accurate, tests. Some of these tests carry a (very small) risk of miscarriage.

"It's fair to say that 95% of women who have the combined screening test get results which are low chance," says Jane Fisher from the charity Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC).

Do I have to have the combined screening test?No. It's completely up to you whether you have it or not. And, if you do decide to have it, you don't have to be screened for all 3 syndromes, if you don't want to.

So, you can choose:

Many pregnant women decide they do want to have the combined screening test because, if it did come back as a high chance, they'd then want to have the other more accurate tests – and, if those came back positive, they could either make a decision about whether to continue with the pregnancy or be prepared for what's to come.

For those who choose not to have the combined screening test, like MFM forum poster Ninja Pigeon, it's often more of a gut decision that knowing more wouldn't make any difference. "We didn't have any testing, over and above the normal ultrasound scan," she says. "We talked about it and we both agreed that we wouldn't terminate whatever, so the tests were redundant.

"But I don't think there's any right or wrong here. It's a very personal choice."

When do I have the combined screening test?You'll be offered this test towards the start of your NHS antenatal care, when you're between 11 and 14 weeks pregnant.

So what exactly does the testing involve? Why is it called 'combined'?"It is called the 'combined screening test' because it combines a nuchal translucency (NT) scan with a blood test," says Nigel Thomson, professional officer for ultrasound at the Society and College of Radiographers. "The NT scan is done (if you consent to it) during your 1st routine ultrasound scan, often called the dating scan or 12-week scan."

The results from the NT scan and the blood test age are then further combined with your age and the gestational age (how many weeks old your baby appears to be, according how long he or she measure, head to bottom, during your scan).

You may have the scan and the blood test on the same day, or they may be done separately.

The blood test is the usual needle-in-the-arm job and may be done by your midwife or a phlebotomist (someone who specialises in taking blood sample). It's common for the blood sample needed for the combined screening test to be taken at the same time as blood is taken for the routine pregnancy blood tests (to check your blood type and so on) – to save jabbing you in the arm twice.

"During the NT scan," says Nigel, "the fluid in the space at the back of your baby's neck is measured by the sonographer who's conducting your ultrasound scan." (Babies with abnormalities tend to accumulate more fluid in this space than average at this stage of pregnancy.)

Occasionally, and usually because of the way your baby is lying, it's not possible for the sonographer to get an NT measurement. If this is the case for you, you should be offered a 2nd scan. If it's still not possible to get a measurement then, you may then be referred for a quadruple test (a different blood test that screens for Down's but not Edwards' or Patau's) or, if your hospital offers it, a NIPT (a newer blood test that screens for dozens of conditions).

When will I get the results?You may be told the NT test result on the day you have your scan. But the length of time it take to give you your final combined test results varies and, obviously, often depends on whether you have the 2 tests done on separate days, and how long your hospital takes to process all the information gathered by the tests.

Generally speaking, you should hear in between 1 to 3 weeks.

What do the results mean?If you're given the NT test result separately, you'll be told the fluid measurement in millimetres: a measurement of 3.5mm or more suggests your baby could be at increased risk of Down's, Edwards' and Patau's.

But the result that really matters is the combined result, and that's the 1 that comes as a 'score'. Well, 2 scores: 1 for the chance of your baby having Down's and 1 for your chance of your baby having Edwards' or Patau's (combined).

"If you are told your chance is between 1 in 2 and 1 in 150, that's considered high," says Jane Fisher. But that doesn't mean your baby definitely has any of the 3 syndromes; it just means you may be offered other, more accurate tests.

Anything over 1 in 151 is considered low. "If you chance is reported as low," says Jane, "it is important to remember that this does not mean your baby definitely does not have a syndrome." It just means it is extremely unlikely – so unlikely, there's no need for further testing.

How accurate are the results? The combined screening test picks up more than 4 out of 5 (85 to 90%) of babies with Down's syndrome, Edwards' syndrome and Patau's syndrome.

But in 2 out of every 100 tests, the result may indicate that your baby has 1 of the syndromes, when he or she doesn't: a 'false positive'.

If I'm told my chance is high, what happens next?You will be offered an appointment with a midwife to discuss going on to have a further, more accurate tests. You don't have to have them if you don't want to.

You may be offered a new screening test called NIPT (also known as cffDNA), which is a blood test that offers a higher degree of accuracy in detecting Down's, Edwards' and Patau's. Some NHS hospitals offer NIPT but others don't yet offer it – although there are plans to starting offering it at all hospitals soon. You may be able to have a NIPT at your hospital if you're prepared to pay; alternatively, you could pay for it at one of the many private clinics that now offer it.

If you don't have NIPT, or if the NIPT result is positive, you are likely to be offered either amniocentesis or CVS – both of which are called 'diagnostic' tests because the results are so accurate (99%) that, if it's positive for Down's, Edwards' or Patau's, doctors will view it as a diagnosis. Both amniocentesis and CVS carry with them a small risk of miscarriage, so you'll have the difficult task of weighing up if it's worth taking that small risk to find out for (almost completely) sure.

Just be reassured that there will be lots of advice and support offered to you along the way. And you may find it helpful to express your feelings on our Chat forum.

Read more:

Pregnant Keke Wyatt Shows Baby Bump After Revealing Trisomy 13 Diagnosis

Showing her pregnancy progress. Two weeks after Keke Wyatt revealed her baby's trisomy 13 diagnosis, the singer gave a glimpse of her baby bump.

Pregnant Keke Wyatt's Family Guide: Meet Her Kids Ahead of 11th ChildRead article

The Indiana native, 40, posed in an animal-print dress in a Saturday, March 26, Instagram Story post, completing the outfit with black heels.

Courtesy of Keke Wyatt/Instagram

Earlier this month, the Marriage Boot Camp alum announced during a performance that her upcoming arrival tested positive for the chromosomal condition, which is characterized by severe intellectual disability and physical defects.

Pregnant Celebrities' Baby Bump Hall of Fame in 2022: PhotosRead article

"I'd like to send a special prayer out for the rude, cruel people that took time out of their day to get on social media and make disparaging and morbid comments concerning my pregnancy," the former reality star wrote via Instagram following the gig. "This past weekend at my show I was very transparent with my amazing fans (who I see as family) about the status of my pregnancy. … For all of the disgusting people out there that are wishing ill on me and my baby. Say what y'all want about me, I'm use[d] to it. No weapon formed against me will prosper anyway."

The R&B Divas: Atlanta alum went on to write that criticizing her "unborn baby" isn't OK, advising the social media trolls to "be careful."

The songwriter concluded, "Be careful putting your mouth on people. I pray that God gives you grace when Life comes knocking on your front door and you won't reap what u are sowing. For all of the POSITIVE stories, emails and support I'm getting THANK YOU! I will not let the negativity drain all of my positive energy. I work hard and my husband and I take care of ALL our children with NO help but GODS OK."

The "Sexy Song" singer and her husband, Zackariah Darring, told her followers in February that they are expecting their second child together, following 2-year-old son Ke'Riah's January 2020 birth.

Wyatt is also the mother of Keyver, 21, Rahjah, 19, and Ke'Tarah with ex-husband Rahmat Morton, as well as Ke'Mar, 11, Wyatt, 9, Ke-Yoshi, 7, and Kendall, 4, with ex-husband Michael Ford. The actress, who is close with Ford's daughter Kayla from a previous relationship, welcomed a stillborn baby while married to Morton. The former couple named the late infant Heaven.

Bode Miller and More Celebrity Parents With the Biggest BroodsRead article

Wyatt's children have "mixed opinions" about another sibling joining the family, she exclusively told Us Weekly last month.

"My kids are very real," the musician said in February. "Overall, they are excited. My kids help me soooo much in every way. Don't get it twisted, some days they are lazy just like kids and I have to get on their ass. But other than that, they are great."

The Ancient Inhabitants Of Northern Iberia Carefully Buried Their Children With Trisomy 21

More than 3,000 years ago, a new group of people arrived in the Ebro Valley. They came from the north and brought new funerary rites with them. They didn't bury their dead, they cremated them. But the excavation of several sites in recent decades has found very young children buried under the floor of houses. From their bone analysis, it was suspected that they had some form of skeletal pathology.

Now, a review based on a new method of analyzing ancient DNA has found chromosomal abnormalities in four of them. Statistically and demographically, such a number is impossible, which leads the authors of the discovery to maintain that "ancient societies likely acknowledged these individuals as members of their communities" and "the burials of the individuals were either special, or performed with care according to standard practices."

A few years ago, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPG, Germany) embarked on an ambitious project that involved searching their enormous database of DNA from ancient humans for the presence of any of the chromosomal trisomies. In such conditions, cells carry three copies of a particular chromosome instead of two: one inherited from each parent.

Of the 23 chromosomes, there are only three non-fatal trisomies: trisomy 21 (which manifests in what is popularly known as Down syndrome), the rare trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), and the even rarer trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome). Given the relatively low prevalence of the syndromes in the population, the scientists needed as many genetic samples as possible from the past. They managed to collect genetic data from 9,855 people who lived between about 5,000 and 400 years ago. Of these, 37 came from young children from two sites in the south of the Navarra region of Spain. The bones had already been analyzed at the beginning of the century, but at that time there was no technology to sequence ancient DNA.

Adam Rohrlach, the lead author of the research that has been published in Nature Communications describes the new method his team used: "We look at the percentage of DNA in a sample that comes from each of the chromosomes and compare it with all the other samples that we have". Next, "we sought to identify those that had approximately 50% more DNA mapping on chromosome 18 or 21, which would indicate an additional copy of the chromosome for an individual," the scientist at MPG and the University of Adelaide (Australia) explains.

With this system, they found seven cases of trisomy among the 9,855 samples they analyzed. They are all very young children. The most recent burial was unearthed in a Christian cemetery in Helsinki (Finland) and dates from the 17th century. The two oldest are from a site in Bulgaria, where they found a six-month-old girl who lived about 4,900 years ago, and the other was from Mycenaean Greece, from which they had samples of another girl of about 12 months of age, who died about 3,300 years ago. The other four come from Spain. Three are from the Alto de la Cruz excavation in the Navarra region, and one child was found at Las Eretas, another site in Navarra. The four set of remains are between 2,800 and 2,400 years old.

The remains of a child who died at 38 weeks of gestation. He had Down syndrome and died between 2,620 and 2,424 years ago in Alto de la Cruz, in present-day Navarra (Spain).Gobierno de Navarra/ J.L. Larrión"Although we have a collection of samples from all over the world, the types of samples from some areas are not comparable to those from others," says Kay Prüfer, a Planck Institute scientist who coordinated the analysis of the sequences. "In particular, the two Spanish sites in our study only have burials of children. This was not normal in the other places where we collected samples," the professor adds. "Given the short life expectancy of people with trisomies in the past, this means we are less likely to find cases where we primarily collect adults. But, in the end, trisomy is so rare that chance also plays an important role," she concludes in an email.

Chance does not seem to fit in the case of the children from the sites in Navarra. They belong to the towns of the so-called Urnfield culture. And they were called that because, because what has been best preserved of them are that, urns with remains of humans cremated in necropolises. Unlike the previous settlers, who buried their dead, these people of probable Indo-European origin cremated their deceased. "But not all of them. Infants were buried in their homes, as if their parents wanted to keep the family together," the archaeologist from the Autonomous University of Barcelona and co-author of the study, Roberto Risch, points out.

But it still doesn't fit. On the one hand, these towns were inhabited for about five centuries. Given the high infant mortality in the past, if the custom was to bury all newborns or deceased babies, there should be many more than those that have been found. Risch maintains that they must have had something special, something that made them different. Since he obtained his degree in the 1980s, this scientist was always intrigued by this very particular funeral ritual. Now, the study of their DNA seems to have proved him right. "These were small communities of 100 to 200 individuals. Given the prevalence of trisomies [in the case of trisomy 21, there is one for every 705 births], more than 1,000 births would have had to occur. "It is statistically impossible," he says. For him, the only explanation is that they reserved the honor of being buried within the walls, under their houses, for the children who had something different.

"Even if they were stillborn or died shortly after birth, they received special treatment. By burying them under the floor, they returned to the family environment"

Patxuka de Miguel, physical anthropologist at the University of Alicante and midwife at Alcoy hospitalPatxuka de Miguel is a physical anthropologist at the University of Alicante. She participated in the first analysis of these children's bones almost 20 years ago together with Javier Armendáriz, the archaeologist from the Public University of Navarra, and both are co-authors of this new study. Even then, they saw that in some cases the bones had abnormalities. This is the case of a 40-week old infant who was found in Alto de la Cruz. But back then there were no genetic tools.

Now it has been learned that he had trisomy 18, also known as Edwards syndrome. This genetic alteration manifests itself in microcephaly, eye and mouth malformations, and clenched hands. "There were malformations in the bones compatible with the syndrome. Now there is no longer any doubt," he says. This is the oldest case of trisomy 18 discovered so far. De Miguel agrees with Risch: "Even if they were stillborn or died shortly after birth, they received special treatment. By burying them under the floor, they returned to the family environment."

Archaeologist Armendáriz recalls that, until the last century, it was common in Navarra and the Basque Country to bury deceased newborns before they had been baptized. This prevented them from being buried in a cemetery, and the deceased child was commonly interred in the eaves of their home. "It may be a practice that comes from then," he says. Remember that 3,000 years ago the funeral ritual for the general population was cremation. "We don't have skeletons from then, except for those of these children," he says. "Not all of them were buried in the houses, but those who were buried were perfectly buried, and some had a trousseau," he adds. The same had happened with the two sets of remains from Bulgaria and Greece. With no obvious relationship with the children of Navarra, they were also buried within the walls of their homes.

The idea of a special and selective burial does not convince Antonio Salas Ellacuriaga, a researcher in Population Genetics in Biomedicine at the Health Research Institute of Santiago de Compostela. In statements to SMC Spain, he argues: "The most obvious limitation, from my perspective, lies in the need to interpret society's perception of people affected by syndromes based on how they were buried." For him, the burial ritual offers only a partial perspective of history. "In addition, given that all the cases the have been identified correspond to early age stages (perinates/neonates/infants), there is the possibility that these individuals had not yet developed distinctive features," the also professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Santiago de Compostela adds, although he did not participated in the study.

However, De Miguel, who in addition to being an anthropologist also works as a midwife at the Verge dels Lliris Hospital in Alcoi (Alicante), maintains that "many of the signs of trisomy are visible and identifiable in newborns, especially after the first cry." What happened to them? Armendáriz points out a possibility: "In the Urnfield culture they would have been treated like others, and like the adults, they would have been cremated."

Between the two sites in this study and the one at Castejón de Bargota (also in Navarra), which does not feature because the scientists did not find children with trisomy, scientists found the remains of 53 children. And they have identified only four with this chromosomal abnormality. To determine with certainty that each of them had something that made them special enough to be buried rather than cremated, the authors say that further research will be needed "to form hypotheses on the cultural practices that may have led to this."

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Comments

Post a Comment