More Ontarians will be flagged for iron deficiency after doctors advocate for change to guidelines

Doctors Urged To Start Testing For 'Fragile X' Syndrome Affecting One In Every 250 Women

GP's across the country are being urged to test patients for Fragile X syndrome - the most common inherited cause of learning disability - with around one in 250 women carrying the abnormal gene.

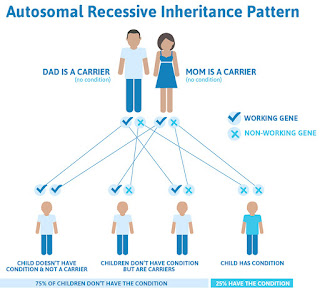

Fragile X syndrome is caused by a genetic mutation that disrupts brain development, which is found in roughly one in 250 women, and one in 600 men. Female carriers are at higher risk of early menopause, and have a 50% chance of passing the condition to their children. Men with the condition will pass it on to their daughters, but not their sons.

The condition affects approximately one in 4,000 males and one in 6,000 females, leading to various developmental issues, Wales Online reports. A charity has called on increased testing amid concerns of a "surprising lack of awareness" about the condition.

Pete Richardson, managing director of the Fragile X Society, says carriers often don't know they're affected. He said: "As the most common inherited cause of learning disability, there is a surprising lack of awareness around Fragile X syndrome. Carriers of the Fragile X pre-mutation often won't know they are affected."

Fragile X affects roughly one in 250 women (Image:

Getty)Those with a family history of Fragile X syndrome, intellectual disability, developmental delay, or autism of an unknown cause, as well as infertility problems, are more likely to be carriers. Women who experience early signs of menopause need to be aware they might be carriers of Fragile X, a condition often overlooked by doctors, said Mr Richardson. He added: "When a woman shows signs of premature menopause, being a Fragile X carrier is often the last thing that doctors will investigate. We need this to change. Now."

For those worried they may have inherited the gene, the Fragile X Society advises seeking out a Fragile X (FMR1) DNA test. Alex McQuade, a 41-year-old mother, became concerned when her son didn't hit his expected developmental stages. Reflecting on her experience, she said: "At no point was there a conversation about genetics, despite myself and husband Chris telling doctors that I had a female cousin with what I thought was an autistic son."

The McQuades, from Groby, Leicestershire, assumed their eldest child's struggles were an anomaly - until their second son started showing similar symptoms. Mrs McQuade said: "I began doing my own research online. I knew it was like autism, but autism didn't quite fit. It wasn't long before I came across Fragile X syndrome. When I found the list of physical symptoms there was no doubt in my mind that the boys had it."

What is Fragile X syndrome?

Fragile X Syndrome is the number one genetic cause of learning disabilities, impacting around one in every 4,000 boys and one in 6,000 girls, Mr Richardson says. "It can cause a wide range of difficulties with learning, as well as social, language, attentional, emotional and behavioural problems.

"The mutation that causes FXS can grow larger when passed on to the next generation, so people with FXS may not have a family history. Also, both girls and boys can have FXS. However, females often have a milder presentation of the syndrome's features."

What causes it?

Mr Richardson says the condition is cauaed by the presence of an abnormal gene. He says: "Fragile X syndrome is caused by a change in the FMR1 gene, and the FMR1 gene is located on the X chromosome.

"This abnormal gene, which can be passed from generation to generation, is usually inherited through the gene that is carried by women. Although both males and females can be FMR1 carriers, and can pass the premutation on to their offspring."

What are the symptoms?

Fragile X has a range of physical, mental and behavioural symptoms (Image:

Getty Images/iStockphoto)Fragile X syndrome manifests in a variety of physical, mental and behavioural symptoms, ranging from mild to severe intellectual disability. Richardson says: "Common behavioural features include short attention span, distractibility, impulsiveness, restlessness, over activity and sensory problems. Learning disabilities occur in almost all males with Fragile X, to differing degrees."

However, some females with the condition can appear less affected, "because females have two X chromosomes, and usually only one of them is affected by Fragile X, the impact of the condition varies. Some females appear unaffected, others have a mild learning disability, and some have a more severe learning disability."

"Girls with or without learning disabilities may show concentration problems and social, emotional and communication difficulties related to extreme shyness and anxiety in social situations."

Physical features associated with Fragile X are often not very obvious in young children, Richardson says, adding: "Physical features include a long face, large or prominent ears, and flat feet which usually become more noticeable in young adults than in children and in males more than females. Males with the condition may also have enlarged testes."

Are carriers of Fragile X at risk of any health problems?

Women carriers often experience early menopause. "Fragile X-Associated Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (FXPOI) is a condition that can affect carrier women under the age of 40," Richardson points out. "Symptoms include decreased or abnormal ovarian function, which can lead to infertility or fertility problems, irregular or absent periods, or premature ovarian failure."

"When a woman shows signs of premature menopause, being a Fragile X carrier is often the last thing that doctors will investigate. We need this to change."

How is it diagnosed?

A DNA test can determine if you're a carrier (Image:

Getty Images)Finding out if someone has the condition can only be done via a DNA test.

"This process is easier if there is an identified carrier already in the family, or someone with Fragile X syndrome and can be arranged by a GP/family doctor, or any physician or genetic counsellor," Richardson said.

How is it managed/treated?

Richardson stresses that although there isn't a cure for the condition, there are treatments available to help alleviate its symptoms.

"Individuals with Fragile X who receive appropriate education, therapy services, and medications have the best chance of using all of their individual capabilities and skills", he said. "Even those with an intellectual or developmental disability can learn to master many self-help skills."

Early intervention is also very important, Richardson adds. This is because a young child's brain is still forming, and so "early intervention gives children the best start possible and the greatest chance of developing a full range of skills."

"The sooner a child with Fragile X syndrome gets treatment, the more opportunity there is for learning."

X Y Chromosomes

In the imprinted brain theory, everyone's brain is configured somewhere on a spectrum between hypomentalism and hypermentalism. In hypomentalism, the mechanistic, paternal genes are over-expressed, creating a baby with a larger head who demands more from the mother; this child is more likely to have autism. In hypermentalism, the mentalistic, maternal genes are over-expressed; the baby is likely to have a smaller head, demand less from the mother, and develop psychosis. The normal brain falls somewhere between the two extremes, ensuring that the child exhibits neither autism nor psychosis.

A Mysterious Syndrome That Paralyzed Kids Seems To Have Disappeared, But Why?

A syndrome that paralyzed children in Colorado and across the nation seems to have disappeared almost as mysteriously as it arrived, leaving scientists to figure out what happened and survivors to adapt as they grow up.

Doctors first identified cases of unexplained muscle weakness and limb paralysis in children, which they called acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM, in 2014—though in retrospect, sporadic cases showed up as early as 2009, said Dr. Kevin Messacar, an infectious disease specialist at Children's Hospital Colorado. The hospital was one of the first to raise alarms that something unusual was going on.

Nationwide, cases spiked again in 2016 and 2018, with only a handful recorded in odd-numbered years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the pattern broke in 2020, possibly because measures to combat COVID-19 kept kids from getting other viruses, and while the most likely culprit virus returned in 2022, the expected cases of paralysis didn't.

Last year, the CDC recorded 18 confirmed cases of AFM, down from a high of 238 in 2018. Colorado has ranged from zero to four cases each year since 2018, when the state recorded 17.

The evidence linking the syndrome to infection by the common respiratory bug enterovirus D68 has only grown, raising questions about whether the virus itself changed, kids' immune systems are responding differently, or some other environmental factor tipped the balance, Messacar said.

Typically, EV-D68 causes colds, but for unknown reasons, it infected the spinal cord and caused muscle weakness and paralysis in a small percentage of kids.

"It may not be as straightforward as one of those three factors," with multiple changes contributing, he said.

No cure exists for AFM, and children who had it vary in how much they've recovered.

Lydia Pilarowski, a 16-year-old who lives in Denver, had one of the earlier known cases in August 2014.

She and her brother both had what seemed like ordinary colds, but Lydia remained lethargic after her brother recovered. Then their mother, pediatrician Dr. Sarah Lacey, started noticing Lydia couldn't do things she did before, like turning while riding her bike or playing the piano with her left hand.

"That's suddenly when it dawned on me that something was wrong," Lacey said.

Certain muscles in her upper arm no longer obeyed her brain's commands to move, so Lydia has worked with occupational therapists over the years to strengthen the other muscles and find creative ways to do the things she wants to.

For example, when she was skiing competitively, Lydia noticed her left arm was dragging in the wind and slowing her down. She initially wasn't sure how people would react to her skiing with her arm in a sling—a clear marker of an otherwise invisible disability—but it improved her times and was freeing in its own way, she said.

"Instead of trying to work through something I can never work through, I work around it and work with it to do the things I love," Lydia said.

The process of learning how to live with the after-effects of AFM never really ends, Lacey said.

As Lydia tries more things, they confront new challenges, such as how to put a suitcase in a plane's overhead bin when one arm won't go over her head. They also recently learned that the syndrome had subtle effects on Lydia's diaphragm, contributing to shortness of breath that Lacey initially thought more cardiovascular training would resolve.

"There are so many things we don't know," Lydia said.

While AFM seems to have gone away as an immediate public health concern for the moment, researchers are still trying to understand it, said Dr. Carlos Pardo, a professor of neurology and pathology at John Hopkins University's School of Medicine.

Right now, one of the top theories is that a different variant of EV-D68 emerged in the early 2010s, causing paralysis in rare cases, he said.

A research lab on the University of Colorado's Anschutz Medical Campus is working on comparing samples of EV-D68 that cause paralysis in at least some cases and others that don't, Messacar said.

They've found only a small number of mutations between the two variants, and are studying whether any of those could have made the critical difference. If they do prove important, that information could help detect if more-dangerous variants return or even lead to new vaccines, he said.

Another possibility is that EV-D68 could always cause paralysis in rare cases. Other syndromes cause the same symptoms, so it could be that doctors simply didn't pick up that a virus might be the root cause, Pardo said.

The syndrome's seeming disappearance also could have at least two possible explanations, Pardo said. Maybe it couldn't hang on during the early years of the pandemic, when people weren't spreading it, and different variants replaced it. Or, maybe enough people now have immunity from a large wave of EV-D68 that the number who are susceptible to that variant dropped dramatically, he said.

While scientists still don't know everything they would like to about AFM, they've made significant progress since 2014, when they didn't even have a test that could detect whether the virus had gotten into someone's spinal fluid, Messacar said. An antibody-based treatment for EV-D68 is going through trials, and more than one possible vaccine is approaching human testing, he said.

Lydia said she hopes researchers can learn more about what caused the wave of AFM cases, both for her own understanding and to prevent something similar from happening again. But that the uncertainty is something she's had to "make peace" with, using the same skills that help her adapt to each new challenge that arises from her disability.

"I think growing up, you have these preconceived notions about what your life will look like," she said. "For me, it's been about embracing the unknown."

2024 MediaNews Group, Inc. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Citation: A mysterious syndrome that paralyzed kids seems to have disappeared, but why? (2024, September 16) retrieved 13 October 2024 from https://medicalxpress.Com/news/2024-09-mysterious-syndrome-paralyzed-kids.Html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Comments

Post a Comment